Table Of Content

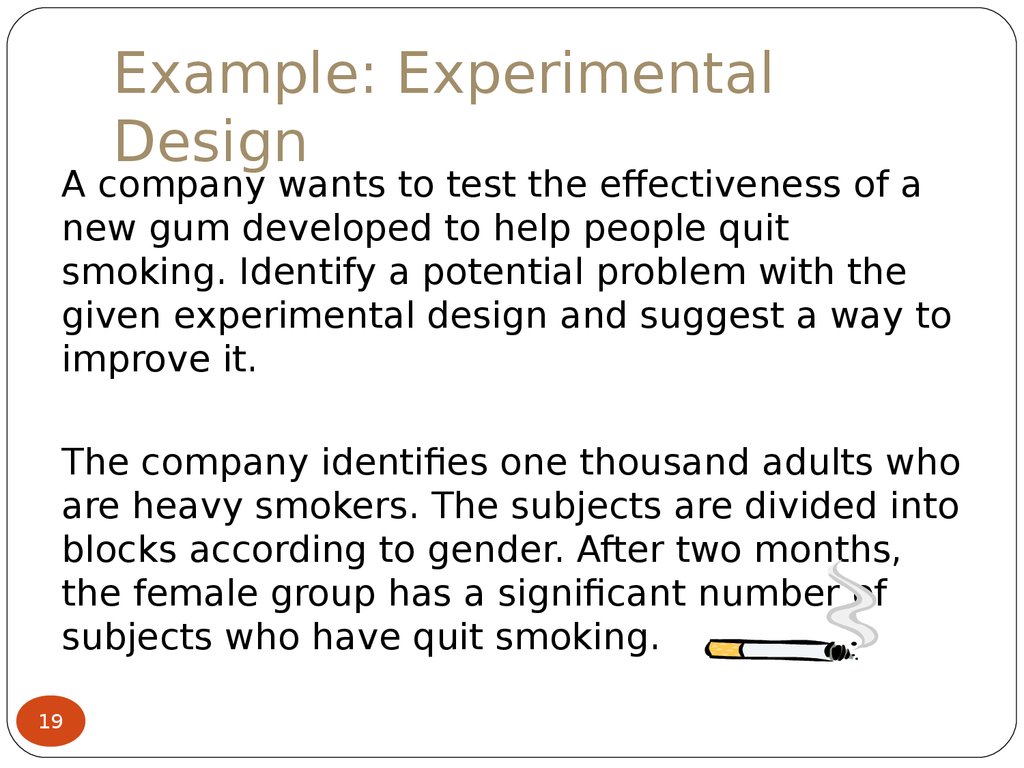

In this article, we will not only discuss the key aspects of experimental research designs but also the issues to avoid and problems to resolve while designing your research study. ANOVA is a statistical technique used to compare means across two or more groups in order to determine whether there are significant differences between the groups. There are several types of ANOVA, including one-way ANOVA, two-way ANOVA, and repeated measures ANOVA. Field experiments are conducted in naturalistic settings and allow for more realistic observations.

Cluster Randomized Design Cons

It allows educators to test new teaching methods and identify what works best. By manipulating variables such as class size, teaching style, and curriculum, researchers can understand how students learn and identify new ways to improve educational outcomes. Similarly, experimental research is used in the field of psychology to test theories and understand human behavior. By manipulating variables such as stimuli, researchers can gain insights into how the brain works and identify new treatment options for mental health disorders.

MULTIVARIATE RESEARCH AND THE NEED FOR STUDY DESIGNS

The upshot is that random assignment to conditions—although not infallible in terms of controlling extraneous variables—is always considered a strength of a research design. In a between-subjects experiment, each participant is tested in only one condition. For example, a researcher with a sample of 100 university students might assign half of them to write about a traumatic event and the other half write about a neutral event. Or a researcher with a sample of 60 people with severe agoraphobia (fear of open spaces) might assign 20 of them to receive each of three different treatments for that disorder.

Extraneous variables (EV)

Only then can they be sure about the effectiveness of their approaches. Some methods they can work with are A/B testing, online surveys, or focus groups. It allows us to test theories, develop new products, and make groundbreaking discoveries. The way you classify research subjects based on conditions or groups determines the type of research design you should use.

Controls Variables

Let the plant exposed to sunlight be called sample A, while the latter is called sample B. Observational studies can be either descriptive (nonanalytical) or analytical (inferential) – this is discussed later in this article. In a Field Experiment, they might change the school's daily schedule for one semester and keep track of how students perform compared to another school where the schedule remained the same. This allows for a more efficient use of resources, as you're only continuing with the experiment if the data suggests it's worth doing so.

Experimental Design Examples (Methods + Types)

In other words, the order of the conditions is a confounding variable. The attractive condition is always the first condition and the unattractive condition the second. Thus any difference between the conditions in terms of the dependent variable could be caused by the order of the conditions and not the independent variable itself. Independent measures design, also known as between-groups, is an experimental design where different participants are used in each condition of the independent variable.

For instance, if you've ever heard of studies that describe how people behave in different cultures or what teens like to do in their free time, that's often Non-Experimental Design at work. These studies aim to capture the essence of a situation, like painting a portrait instead of taking a snapshot. Non-Experimental Design has always been a part of research, especially in fields like anthropology, sociology, and some areas of psychology.

Wait List Control Groups in Psychology Experiments - Verywell Mind

Wait List Control Groups in Psychology Experiments.

Posted: Mon, 18 Dec 2023 08:00:00 GMT [source]

Importance of Experimental Research Design

The Key to Creating Cost-Effective Experiments at Scale - Behavioral Scientist

The Key to Creating Cost-Effective Experiments at Scale.

Posted: Tue, 03 Apr 2018 07:00:00 GMT [source]

Born out of the early 20th-century work of statisticians like Ronald A. Fisher, this design is all about control, precision, and reliability. Those are the basic steps you need to follow when you're designing an experiment. Each step helps make sure that you're setting up a fair and reliable way to find answers to your big questions. Fast forward to the Renaissance (14th to 17th centuries), a time of big changes and lots of curiosity. People like Galileo started to experiment by actually doing tests, like rolling balls down inclined planes to study motion. He'd have an idea, test it, look at the results, and then think some more.

It is also important to mention what precautions have been taken to minimize any risks. In essence, failure to meet the ethical norms may question the validity of your research study and objectives. No study is perfect, and a researcher needs to identify those limitations and incorporate them into the research design and findings. Moreover, including a statement in your manuscript about any interpreted limitations would help you to substantiate your conclusion. Not including the limitations would be construed as an error on the part of the researcher.

Since researchers aren't controlling variables, it's hard to rule out other explanations for what they observe. It's like hearing one side of a story—you get an idea of what happened, but it might not be the complete picture. For example, if ten different studies show that a certain medicine helps lower blood pressure, a meta-analysis would pull all that information together to give a more accurate answer. In the world of experiments, the True Experimental Design is like the superstar quarterback everyone talks about.

In forward-direction studies, the researcher starts with determining the exposure to a risk factor and then assesses whether the outcome occurs at a future time point. For example, a researcher can follow a group of smokers and a group of nonsmokers to determine the incidence of lung cancer in each. In backward-direction studies, the researcher begins by determining whether the outcome is present (cases vs. noncases [also called controls]) and then traces the presence of prior exposure to a risk factor. For example, a researcher identifies a group of normal-weight babies and a group of low-birth weight babies and then asks the mothers about their dietary habits during the index pregnancy.

In a factorial design, participants are randomly assigned to one of several groups, each of which receives a different combination of two or more independent variables. Have you ever interrupted your reading of the “Methods” to sketch out the variables in the margins of the paper as you attempt to understand how they all fit together? Or have you jumped back and forth from the early paragraphs of the “Methods” section to the “Statistics” section to try to understand which variables were collected and when? These efforts would be unnecessary if a road map at the beginning of the “Methods” section outlined how the independent variables were related, which dependent variables were measured, and when they were measured. When they were measured is especially important if the variables used in the statistical analysis were a subset of the measured variables or were computed from measured variables (such as change scores).